Batman, still the greatest superhero of all time (sorry Spider-Man), has a rich history deeply infused with horror influences. From his inception in the late 1930s to his modern-day adaptations, the Dark Knight’s world has consistently drawn from horror – and psychological horror cinema in particular. His origins and rogues gallery each reflect the history of the cinematic macabre, and draw from a range of psychological conditions, creating a unique blend of superhero and horror genres.

This connection is evident from Batman’s earliest days. The character’s creation by Bob Kane and Bill Finger was heavily influenced by the dark, gothic atmosphere of horror films from the 1920s and 1930s. Kane and Finger drew inspiration from movies like The Bat Whispers (1930) and Dracula (1931). The shadowy, brooding aesthetic of these films helped shape Batman’s persona as a nocturnal avenger lurking in the shadows.

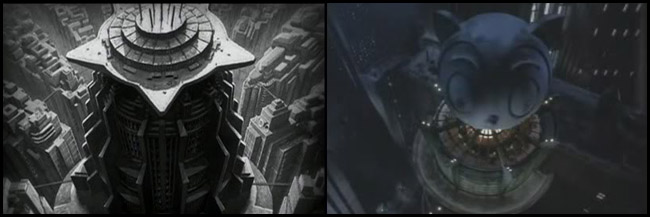

In more recent adaptations, directors like Tim Burton and Matt Reeves have embraced these horror elements. Burton’s Batman (1989) and Batman Returns (1992) are filled with gothic imagery and grotesque villains, reminiscent of classic horror films – in particular those of German Expressionism. The brooding skylines of Burton’s Gotham reflect the sinister rooftops of Berlin in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), and the juxtaposition of psychiatric concerns and starkly foreboding architecture draws from the German tradition.

Reeves’s The Batman (2022) takes this a step further, drawing inspiration from David Fincher’s horror-thrillers Se7en (1997) and Zodiac (2007) to create a dark, threatening atmosphere – existing, once again, in the shadow of insanity. Paul Dano’s portrayal of the Riddler as a serial killer echoes the chilling realism of this strand of cinema, blending the superhero genre with psychological horror.

In all these cases, Batman is framed as the hero of a psychiatrically disordered realm. His own behaviour is a disjunction of personality in response to trauma – the shooting of his parents is often criticised as a plot point that is needlessly returned to again and again in his cinematic incarnations, but this reflects the PTSD-like quality of its impact. His response to this primal wound is to split his personality into Bruce Wayne and The Batman – a dissociation so severe that even when bound by Wonder Woman’s magical lasso of truth, in one comic, he gives his true identity as “Batman.”

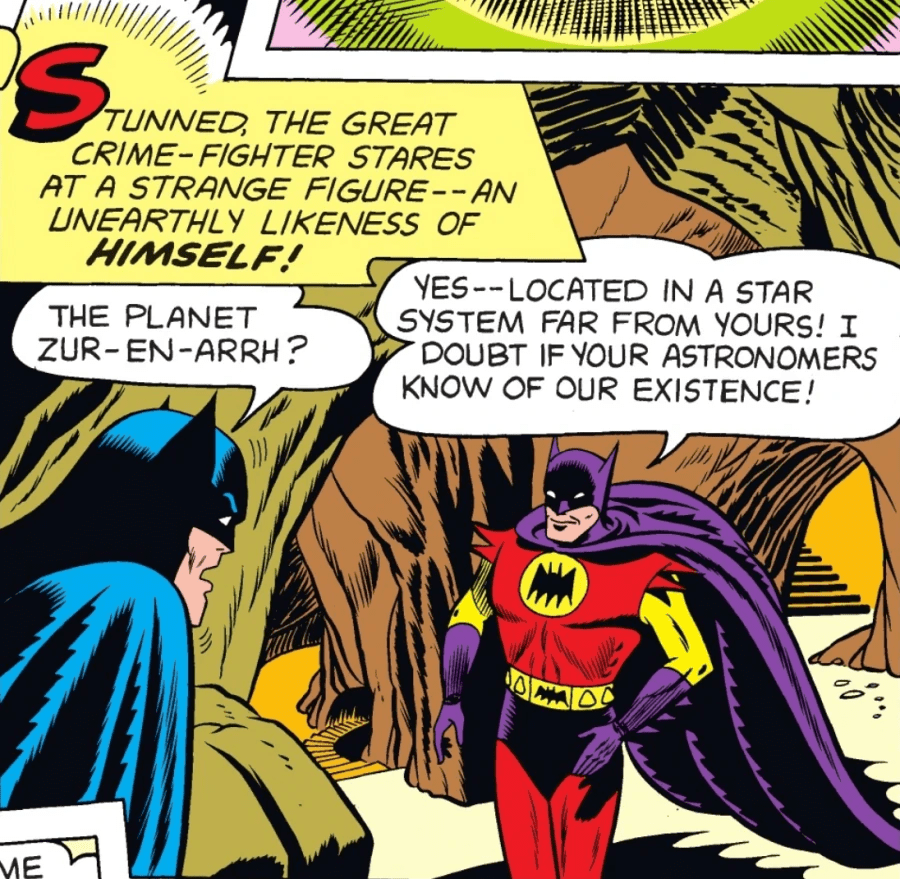

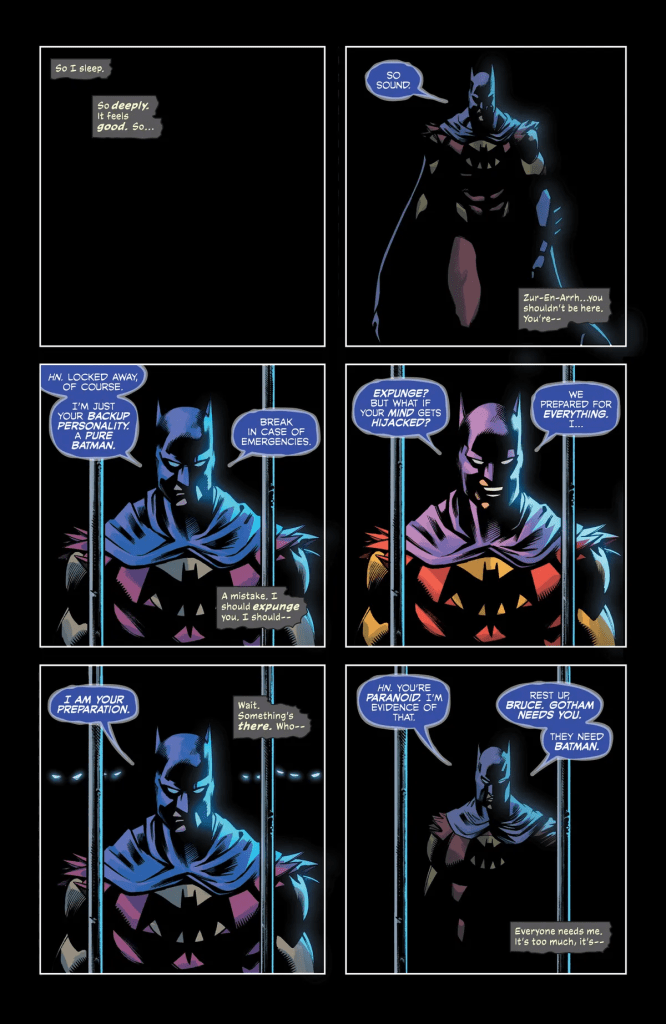

This dissociation is so useful to Batman, in fact, that in one story he deliberately seeks it – when villain Dr Hugo Strange attempts to break him psychologically, he switches persona to “The Batman of Zur-En-Arrh”, a backup personality it is revealed he had previously programmed himself as a defence mechanism against psychological attack. That character had previously been introduced in a particularly silly silver-age story, but writer Grant Morrison reimagined that as a hallucinatory byproduct of Batman’s self-directed brainwashing manoeuvre.

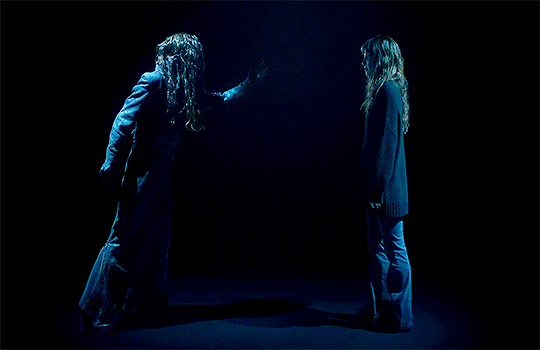

That said, alternate personalities can be hard to control. In James Wan’s Malignant (2021), heroine Madison and villain Gabriel literally share a body and brain, and at the climax Madison must stare Gabriel down inside a psychological void, and imprison him, in order to take control of herself. This framing was mirrored in Batman’s 2023 Gotham War storyline, in which Batman’s alternate lives on… and appears to be more than just a tool, with a menacing presence that serves as a classic horror setup for nightmares to come.

Batman may (or may not) have made Dissociative Identity Disorder work for him on that occasion, but his general failure to achieve Jungian integration would be tragic if it wasn’t for the fact that his world and its society mirrors his own disorder – in an insane world, to be well adjusted would be the true insanity. His world makes his excuses for him. To that point, Batman’s rogues gallery is a testament to the influence of horror on his mythos. Many of his villains are inspired by classic horror archetypes, psychological disorders, or both – each embodying different aspects of fear and madness.

The Joker is perhaps the most iconic of Batman’s foes, Defined by his insanity, the Joker’s unpredictable nature and lack of empathy make him a terrifying figure, embodying the horror of a mind completely unhinged. Sometimes played as an anarchist, mobster, terrorist or nihilist, but most often as an absurdist, the Joker’s design and character are heavily influenced by horror. His appearance is based on Conrad Veidt’s character in The Man Who Laughs (1928), a film steeped in German Expressionist horror. His chaotic nature and penchant for gruesome crimes make him a figure of terror in Gotham City – and one who claims, ominously, that insanity can take over anybody on the basis of :one bad day” – ripping a person from the frame of societal norms and leaving them with nothing to do but amuse themselves, with justice and normalcy being the ultimate jokes.

Burton, meanwhile, preferred to show the Joker as a manic-depressive art lover. In Batman (1989), Jack Nicholson plays the role as a man who just wants to have fun – and what could be more fun than the gleeful destruction of everything Gotham holds dear? As he dances around to his own personal soundtrack, his euphoria is clear – as is his desire to rework the city into a reflection of his own deranged persona – a seemingly clear case of anti-social behaviour disorder and narcissistic personality disorder. The cinematic references continue as he disfigures Jerry Hall’s character with acid and gifts her a Phantom of the Opera style porcelain mask.

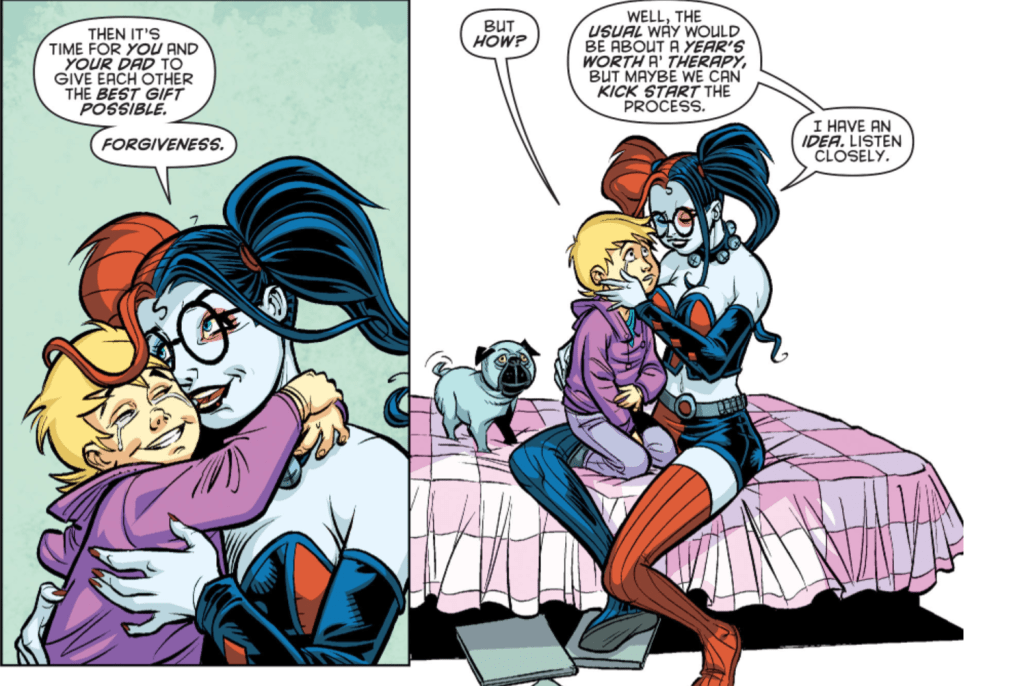

Originally a psychiatrist at Arkham Asylum, Dr Harleen Quinzel’s descent into madness as ‘Harley Quinn’, after falling in love with the Joker, further highlights the horror of losing one’s sanity. Her transformation from a respected doctor to a deranged criminal is both tragic and terrifying – and reflects a key theme of psychological horror in which the fear of losing one’s sanity lurks around every corner. From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and A Page of Madness (1926) through films like Asylum (1972), the terror of losing one’s mind through influence from the insane in an asylum setting is a longstanding theme of psychiatric horror cinema, and what better place to explore that than in Gotham’s legendary Arkham Asylum? And yet in modern versions, Quinzel has thrown off the Joker and reinvented herself, even forming a relatively healthy relationship with Poison Ivy. This partial success in re-integration, moving from thesis (Quinzel) to antithesis (Quinn) to her current synthesis is a rare example of a psychiatric success story in Batman’s gallery. Perhaps her current form is Quinn’s true self, unleashed and unafraid.

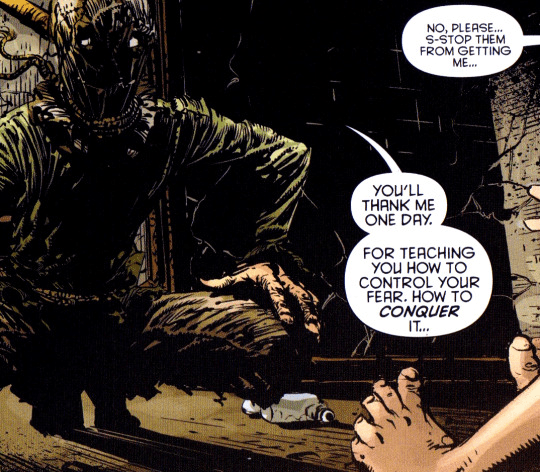

Jonathan “The Scarecrow” Crane’s obsession with fear and his use of fear toxin to manipulate his victims reflect his own deep-seated psychological issues. His character explores the horror of phobias and the power of fear as his weapons, employing a fear toxin to induce nightmarish visions in his victims. His creation drew heavily from Washington Irving’s tale of fear The Legend of Sleepy Hollow, even sharing his surname with the hero of that story. The classic horror trope of the mad scientist is also a strong influence, with the sinister effects of Crane’s chemical ‘fear-toxin’ experiments reflecting classic mad doctor characters such as Dr. Jekyll. Meanwhile the psychological horror of hallucination and being overtaken by one’s deepest fears is a classic trope, with modern incarnations of the character bearing the marks of Repulsion (1965) and Jacob’s Ladder (1990) . Portrayed by Cillian Murphy in the Christopher Nolan Batman movies, he makes one unforgivable error – he refers to “the Scarecrow” as a Jungian archetype. Sorry Nolan, but that is nonsense.

Originally a horror actor turned serial killer, Basil Karlo (the first Clayface) is a direct nod to horror cinema – even his name mirrors that of Boris Karloff. His ability to shapeshift into monstrous forms adds a body horror element to Batman’s rogues gallery, and subsequent versions of the character have carried this aspect forward. Clayface is typically presented as a tragic monster with the competing motivations of revenge and a desire for understanding – an unstable position that places him in the tradition of Frankenstein. To more modern audiences, in modern incarnations, the abhorrent malleability of his flesh can be positioned as positively Cronenbergian.

Although the Penguin and Catwoman are classic Batman villains driven more by greed than irrationality, Tim Burton repositioned them in Batman Returns as more horror-driven variations on their traditional personas. Danny DeVito’s portrayal of the Penguin is a grotesque, almost monstrous figure, with his deformed appearance, sexual insecurity, kinship with animals and references to himself as a “freak” all pointing to Tod Browning’s horror classic Freaks (1932), whilst also dressing him as Dr. Caligari. McDonalds were understandably concerned when they saw the image on which they’d paid millions of dollars to slap on their happy meals.

Meanwhile Selina Kylie is re-positioned away from the jewel thief of her earliest appearances, or the street-tough sex worker of her later incarnations, to be a sexualised amnesiac whose persona is a response to the un-integratable trauma of being abused by the patriarchy – most clearly represented by Christopher Walken’s Max Schreck (named after the actor who played the title character in Nosferatu (1922). Schreck is himself a form of capitalist vampire, draining not just money from the population, but power – via a giant capacitor that’s set to absorb and re-sell energy from Gotham’s electric grid.

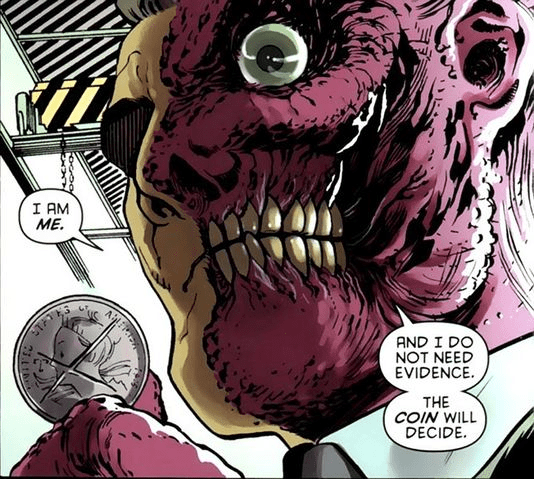

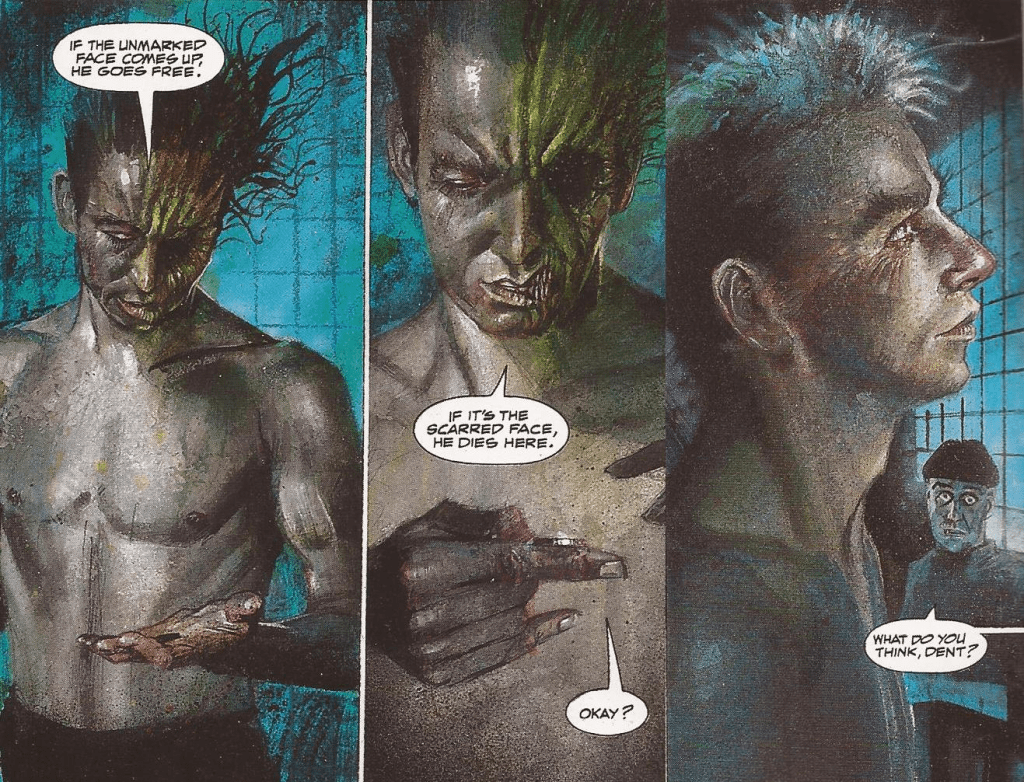

Unlike Catwoman, District Attorney Harvey Dent’s transformation into ‘Two-Face’ has always been an example of both Dissociative Identity Disorder horror, albeit mixed with a degree of body horror. Again we see a character’s personality disorder as a direct result of his trauma, with Dent’s internal struggle between his competing personas another failure of psychological integration – and again the spectre of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Doctor Jekyll and Mister Hyde looms large.

All of the rogues listed above have been represented in Batman’s various cinematic embodiments, but Batman has possibly the deepest bench of villains in comics history, and there are plenty of examples that bear the influence of horror that haven’t yet made it to the big screen themselves. Jervis Tetch, aka the Mad Hatter, suffers from delusions and obsessive-compulsive disorder. His monomaniacal fixation on Alice in Wonderland and his mind-control devices add a surreal, almost dream-like horror to his character. Mind control by malign influencers is another key theme of The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari, as well as other early horrors like Svengali (1931) and Fritz Lang’s Dr Mabuse films.

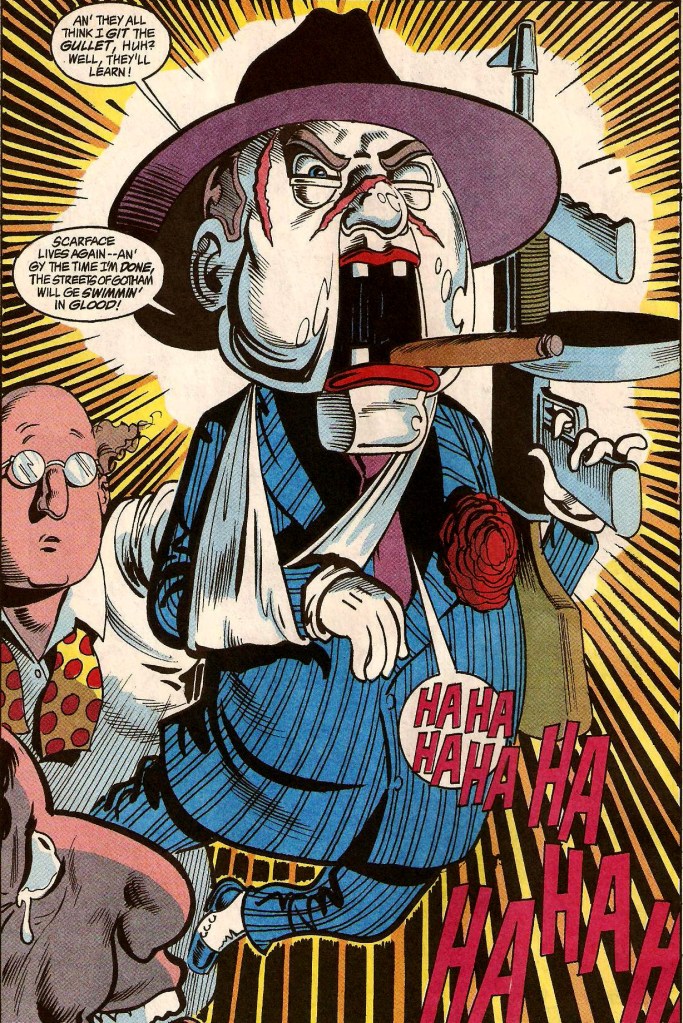

The Ventriloquist, meanwhile, is yet another dissociating villain, who pushes his unacceptable desires for power and riches onto his mobster doll, Scarface – himself a classic cinema reference, to Scarface (1932). Sinister ventriloquist dummies that consume their handlers’ minds are a classic horror trope, from Dead of Night (1945) to Magic (1978) and beyond – a fact certainly on creator John Wagner’s mind when he devised the character in 1988.

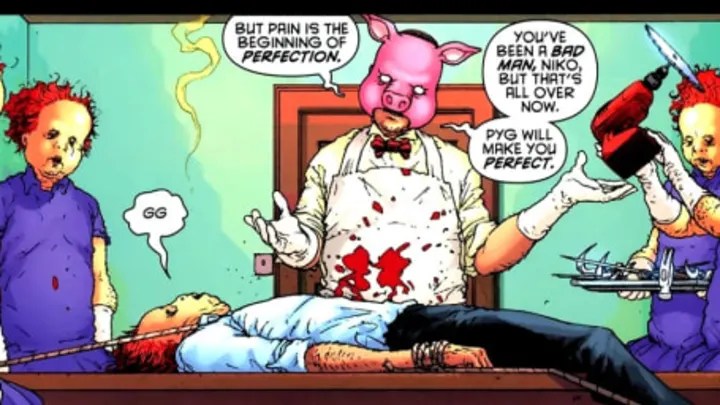

Finally, Professor Pyg, whose real name is Lazlo Valentin, is a deranged and sadistic villain in the Batman universe. He is known for his grotesque surgical experiments, where he transforms his victims into mindless, doll-like creatures called Dollotrons. Pyg wears a pig mask and often uses surgical tools as weapons, adding to his terrifying persona.

Pyg, created by Grant Morrison, is the most recent of the villains in this article, first appearing in “Batman #666” (July 2007). Morrison drew inspiration from various sources, including horror films and psychological thrillers, to create a villain that embodies both physical and psychological horror. The character’s name is a reference to the Pygmalion myth, where a sculptor falls in love with a statue he created, reflecting Pyg’s obsession with “perfecting” his victims.

Professor Pyg is one of Batman’s most disturbing villains, and draws inspiration from several horror cinema elements. His deranged surgical experiments on his victims are reminiscent of various mad doctor films, combined with the influence of serial killers such as Ed Gein, and the Gein-influenced horror films The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974): The grotesque and brutal nature of Leatherface, who wears a mask made of human skin, parallels Professor Pyg’s use of a pig mask. His obsession with creating ‘perfect’ Dollotrons references both Jeffery Dahmer’s real-life attempts to create obedient zombies from his victim, and the classic French horror Eyes Without A Face. That film, about a surgeon who kidnaps women to graft their faces onto his disfigured daughter, mirrors Pyg’s gruesome surgical attempts to create ‘perfect’ humans. Those Dollotrons also bring to mind the animatronic band from The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1972).

Pyg is an unusually brutal and disturbing example of a Batman rogue, but in general the psychiatric conditions of Batman’s adversaries various are often exaggerated to horrific extremes, raising the issue of whether these fictional creations might stigmatise real life conditions, simplifying and vilifying these psychological disorders by displaying them at these most extreme and implausible, and associating them with moral corruption. As the gag goes, can it be right to derive entertainment from a billionaire punching people with mental illness into submission? It seems there are two ways to resolve this conundrum – either make the characters so monstrous as to remove them from meaningful comparison with more typical psychiatric patients, as with Professor Pyg, or alternatively make them into sympathetic figures, searching for ways to exist as their authentic selves in a world that rejects them, forced by circumstances into ‘villainy’. This is the case with most modern portrayals of Quinzell, and in fact most of Batman’s rogues have had stories in which they embraced and mastered their conditions and through that achieved a degree of redemption. In Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House On Serious Earth, Batman is ultimately saved by Two-Face, who masters his iconic disfigured coin to take control of his own decisions.

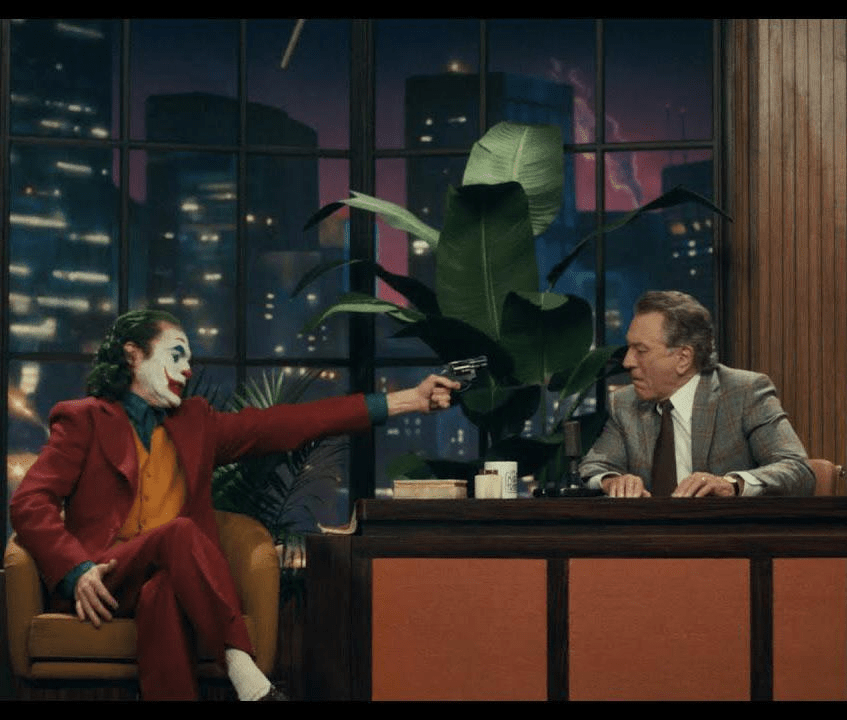

However, this can raise a new form of danger – what if a villain is made ultimately sympathetic in that way, but nonetheless remains lethal to the public? This is the issue with Todd Phillip’s Joker (2019) in which Joaquin Phoenix’s take on the titular character is a tragic anti-hero rejected by society for harmless reasons he cannot control, who nonetheless responds to that alienation by shooting a chat show host on live television. Drawing shamelessly from Martin Scorsese’s The King Of Comedy (1982), this version of the Joker is more lethal and more sympathetic than that film’s Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Nero, who also appears as Joker’s chat show host in a typically clumsy bit of hommage). This approach replaces vilification with a questionable degree of implicit approval – where Matt Reeves’ The Batman used The Riddler to ridicule and ‘other’ contemporary incel radicals, Phillip’s film seems to embrace the logic of the school shooter – push me away once too often and face the punishment.

For better or worse then, the horror influences on Batman’s history, world, and adversaries have helped shape him into a unique character who straddles the line between superhero and horror icon. Whether it’s the gothic atmosphere of Gotham City, the nightmarish villains he faces, or the psychological depths of his own mind, Batman’s world is one where a hero fights horror with horror, and wins – but at what cost?