Once upon a time, I went to see a ghost story – or rather A Ghost Story (2017), David Lowery’s exploration of time and grief. I enjoyed it enormously. The couple in front of me, however, had a more mixed response to the sight of Casey Affleck drifting through time covered in a morgue sheet while Rooney Mara wolfed down an entire pie: she loved it, but he disliked its pacing, its oblique, minimal plotting, and its drifting ambiance. She explained that those were the very things she loved most. He huffed that, well, that’s no surprise, after all “…you like shoegaze.”

Shoegaze was a rock genre that emerged in the early 1990s, when bands like Chapterhouse, Ride, My Bloody Valentine, Slowdive and Lush unleashed waves of layered, dreamy drone rock that took their audiences into a trance. Rejecting a focus on themselves as performers, the bands had a tendency to seemingly disengage from the crowds and gaze down at their effects pedals and taped lyric sheets. Journalists coined the term shoegazing, which the bands mostly hated. But the sweeping, dreamy neo-psychedelia laid the foundations for the ambient and post-rock sounds of everyone from Sigur Ros to Mogwai. This was music that took you out of yourself.

A Ghost Story is by no means the only horror (or horror-adjacent) film to have a comparable hypnogogic quality. Starting from around the time of Panos Cosmatos’s Beyond The Black Rainbow (2010) there came a slow wave of these films extending through A Ghost Story to more recent examples like Skinamarink (Kyle Edward Ball, 2022). At their core, these films are horror movies, but for the most part they reject traditional horror tropes and shocks in favor of a kind of sublime, unsettling otherness.

Taking these films together as Shoegaze Horror, their defining qualities are:

- Ambiguity: Shoegaze horror is not about clear answers—it’s about the sensation of unease, nostalgia, and the inexpressible.

- Slow, Lingering Mood: The camera lingers on empty rooms, static shots, and long dissolves to let the mood sink in.

- Repetition & Loops: Many of these films use recurring motifs, sounds, and images to create a hypnotic, shoegaze-like effect.

- Liminal Spaces: Whether it’s a quiet house, an empty road, a backstage green room or a foggy dreamscape, these films place characters in in-between places where reality feels unsteady.

- Auditory Dread: Long silences and muffled sound design create a feeling of helpless passivity in the face of horror.

Just as shoegaze music layers distortion, reverb, and hazy vocals to create an immersive soundscape, these films use cinematography, sound design, and slow pacing to orchestrate a creeping, immersive horror experience. The overall impact is a sense of depersonalisation and derealisation.

As for why such a feeling should start pushing through the culture after 2010, perhaps it was (and is) a sign of post-financial crash social malaise – a cinema for a generation whose direction seems to have dissolved away, leaving them haunted by lost possibilities. More recently, many Covid sufferers were left with a lingering sense of being submerged into a semi-conscious state where time flowed differently – a feverish fugue while their swelling brains were mildly pulped. More broadly, the Covid lockdown era familiarised audiences with the strange psychological effects of enforced isolation and lack of personal momentum. Perhaps Shoegaze Horror is the cinema of hauntology – of dead futures that loop back endlessly into the past.

A Shoegaze Horror Starter Pack

If you’re looking for a place to start with Shoegaze Horror, here is a selection of films that best typify the range of the genre. This is a cinema of atmosphere, distortion, and eerie melancholy and these films exemplify its key traits – dreamlike, detached, and hypnotically immersive.

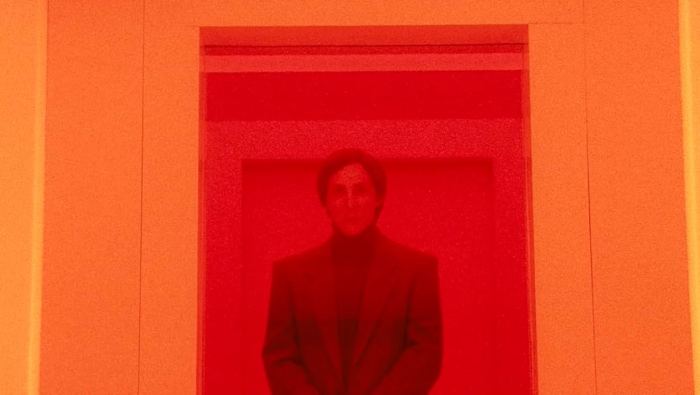

1. Beyond the Black Rainbow (Panos Cosmatos, 2010)

In 1983, a young woman with telepathic abilities is held captive in a sinister research facility, in this dreamlike, slow, and hallucinatory horror film, drenched in neon paranoia and meditative dread. A synth-heavy ambient score, and slow, meditative pacing, combine to make Beyond The Black Rainbow trippy, claustrophobic, and as nostalgic as a decaying VHS tape.

2. Berberian Sound Studio (Peter Strickland, 2012)

A British sound engineer working on an Italian horror film slowly loses his grip on reality as the distinction between sound, memory, and film disintegrates. Using layered ambient noise, repetition, droning effects, and suffocating liminality, Berberian Sound Studio‘s horror is auditory, internal, and hypnotic. It loops into itself like a warped, scratched vinyl record. The effect is oppressive, dreamlike, and paranoid—a slow breakdown into pure sound. Sound design is key in Strickland’s work, and he is a key trailblazer for ASMR horror.

3. Under the Skin (Jonathan Glazer, 2013)

An alien disguised as a woman (Scarlett Johannsen) hunts unsuspecting men in Scotland. This detached, eerie, and existential sci-fi horror favours mood and alienation over emphasising its bare-bones plot, which was heavily cut back from the source novel. Cold, hypnotic, and distant—like floating through someone else’s dream – Under The Skin‘s ethereal visuals, droning ambient sound design, and gorgeous Mica Levi score make it quintessential shoegaze horror.

4. It Follows (David Robert Mitchell, 2014)

A supernatural entity relentlessly follows a young woman after a sexual encounter in this soft-focus, pastel horror that features an unstoppable sense of doom creeping in from the edges. The effect is nostalgic yet surreal—like a fever dream of late-summer suburban dread, all bolstered by Mitchell’s use of a retro synth score, soft camera work, and an eerie sense of inevitable fate. And that dreamy clamshell e-reader!

5. I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House (Osgood Perkins, 2016)

A live-in nurse begins to suspect the house she’s caring for is haunted, in this slowest of slow-burn ghost stories. Oz Perkins’ most underrated film is minimalist, eerie, and quiet horror, built entirely on mood and slow decay. With muted color grading, hushed narration, and a ghostly stillness, I Am The Pretty Thing That Lives In The House is whispery, ethereal, and haunted—like a forgotten voice in an empty room.

6. Personal Shopper (Olivier Assayas, 2016)

A grieving high-fashion personal assistant, with a talent for communicating with spirits, wanders through Paris in search of a sign from her recently deceased twin brother. As she navigates her lonely existence, a series of eerie messages on her phone hint at something watching her. A quiet, meditative, and emotionally distant film, with long, observational sequences that drift between loneliness and the uncanny. Ghosts are treated as a potential presence, not a source of jump scares. It’s true that the soundtrack is more classical than the synth-y drone of many other films on this list, but it’s desolately minimal – and Assayas’s detached, weightless cinematography mirrors the protagonist’s emotional alienation.

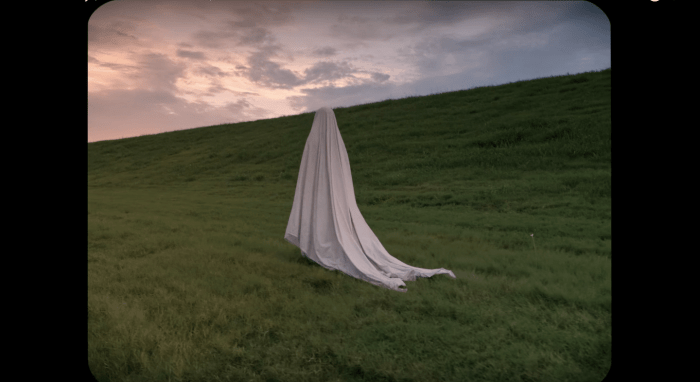

7. A Ghost Story (David Lowery, 2017)

A recently deceased man’s spirit lingers in his former home as time moves on, in this haunting meditation on time, loss, and impermanence, where the ghost’s presence is felt through silence and space rather than action. A Ghost Story is quiet, cosmic, and emotionally vast. Its lingering shots, ambient score, and poetic, dreamlike structure create afeeling of watching grief dissolve into the eternal.

8. Starfish (A.T. White, 2018)

A grieving woman wakes up to find the world has ended, leaving her alone in an abandoned town filled with cryptic signals and echoes of the past. A.T. White’s elegiac, meditative apocalypse is a film about loss, memory, and the spaces left behind, unfolding in fragments of quiet devastation. With soft, snow-drift cinematography, a dreamlike indie soundtrack, and a drifting, introspective pace, Starfish is wistful, isolating, and otherworldly, as if we are tuning into a radio signal from a vanished world.

9. Lux Æterna (Gaspar Noe, 2019)

Two actresses, Charlotte Gainsbourg and Béatrice Dalle, prepare to shoot a film about witch persecution – but as technical failures, psychological manipulation, and escalating conflicts push the boundaries of reality, the shoot descends into a nightmarish, strobe-lit sensory overload, blurring the line between performance and real-life hysteria. If most Shoegaze Horror films deliver a sense of soft, liminal melancholy, Lux Æterna represents shoegaze’s harsher, feedback-heavy, psychedelic edge—closer to a noise-heavy My Bloody Valentine live performance than a Slowdive track. The final sequence, with its flashing RGB strobe lights, engulfs the audience in a relentless assault of colour and noise. Noe burns our our retinas, plays Chopin’s funeral march backwards, and delivers on his promise of euphoria – as narrative dissolves into pure sensation.

10. Come True (Anthony Scott Burns, 2020)

A teenager joins a sleep study, only to find nightmares bleeding into the waking world, in this synth-drenched dream horror. Come True is a neon-lit sleep paralysis terror, where reality bends into eerie, inescapable dreamscapes. Muted lighting, VHS grain, and a synth-heavy, reverb-drenched score mean that this shoegaze cousin to Nightmare on Elm Street is hypnotic, dark, and suffocating; its heroine trapped inside a decaying video dream.

11. She Dies Tomorrow (Amy Seimetz, 2020)

A woman is overcome with the unshakable belief that she will die tomorrow, and her existential dread spreads like a virus in this anxiety-horror about the weight of inevitability, where the fear of death is as contagious as a melody stuck in your head. Ethereal visuals, dreamlike pacing, and a trance-like atmosphere make Seimetz’s debut feature hypnotic, creeping, and surreal; a panic attack unfolding in soft colors.

12. We’re All Going To The World’s Fair (Jane Schoenbrun, 2021)

Schoenbrun’s drone-infused film follows a lonely teenager who immerses herself in an eerie online role-playing game. Lingering in dimly-lit rooms and upon flickering screens, and probing the boundaries between reality and digital folklore. An unsettling ambient soundscape generates a slow-burning unease that amplifies its themes of isolation, dissociation and transformation, in a quasi-horror film that thrives on liminality, existential dread and hypnotic sonic textures rather than traditional shocks.

13. Skinamarink (Kyle Edward Ball, 2022)

Two children wake up to find their parents gone and their home shifting into an inescapable void, in this film about the horror of memory, absence, and space, where childhood fear becomes a formless nightmare. TikTok fave Skinamarink‘s grainy, lo-fi visuals, near-silent soundscape, and a detached, dreamlike structure underscore a film that’s abstract, quiet, and unsettling—a liminal drone horror that feels like being lost in the shadows of a childhood memory.

14. New Religion (Keishi Kondo, 2022)

A grieving woman is drawn into a surreal and eerie world of body horror and religious symbolism in this elliptical horror film that unfolds like a slow, dissolving dream. Blending spirituality, technology, and grief, New Religion is hypnotic, spiritual, and deeply melancholic, with soft-focus cinematography, poetic imagery, and an eerie, droning score.

15. In a Violent Nature (Chris Nash, 2024)

A mute supernatural killer is resurrected in the wilderness and stalks a group of teens, in Chris Nash’s ambient slasher. Suffused with ambient natural sound, and lingering dread he looming violence is slowed to an unsettling stillness that feels meditative, unsettling, and voyeuristic – a film that I compared to Tsai Ming-Liang’s Friday The 13th Part 6, and that’s also been called a Jason Voorhees Walking Simulator.

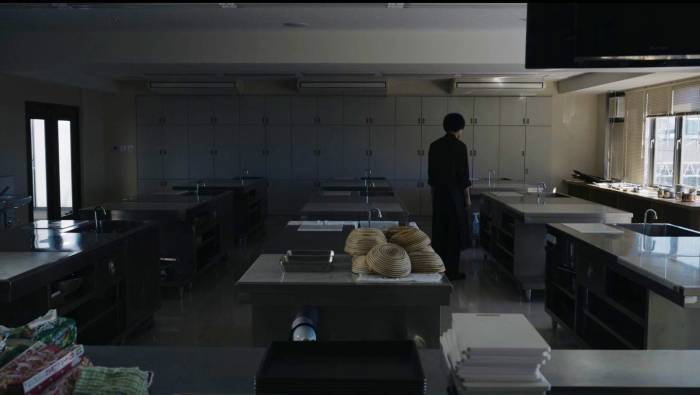

16. Chime (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2024)

A schoolteacher’s life is disrupted by a mysterious chime, leading to an increasing sense of dread and surreal experiences. Kurosawa’s return to horror unfolds in a small set of alienating environments filled with creeping dread. Its unsettling stillness and cryptic narrative create a lingering sense of unease. Eerie, atmospheric, and introspective, with one of Kurosawa’s signature ambient soundscapes, Chime presents the audience with a texture of jittery anxiety.

17. Presence (Steven Soderbergh, 2024)

Told entirely from the perspective of an unseen ghost, Presence follows a spirit quietly observing a grieving family, particularly their teenage daughter, Chloe, as the boundaries between past and present dissolve. Soderbergh’s restrained direction, fluid, detached camerawork, and ambient minimalism evoke a dreamlike, weightless experience. With long, meditative takes, muted performances, and a looping, spectral score, the film generates a sense of time overlaying itself – embracing loss, time, and distance vs closeness as its core themes.

The Themes of Shoegaze Horror

From the films listed, the shape of Shoegaze Horror’s deeper preoccupations emerges.

1. Memory, Time, and the Ghostly Echoes of the Past

Many of these films deal with time as a haunting force, where characters are trapped in memories or unable to move forward. Time feels cyclical, looping back on itself like an old, half-forgotten melody. Soft-focus visuals, muted or washed-out color palettes, lingering shots of empty spaces, and droning ambient scores that give a sense of eternity.

- A Ghost Story → A ghost literally lingers in the same space for what feels like eternity, observing life pass by in silence.

- Starfish → Grief and nostalgia collide as the heroine navigates an abandoned world filled with remnants of the past that nevertheless feel faded, distant and unreachable.

- Skinamarink → The past and present blur into a child’s surreal nightmare, where the sense of “home” fades into nothingness.

- New Religion → Grief and trauma become a spiritual and bodily experience, as if the past can physically alter a person.

- Presence → A spiritualist medium brought in by the family emphasises that time works differently for ghosts, with past and future jumbled together.

2. Isolation, Loneliness, and Alienation

A key emotional undercurrent in shoegaze horror is isolation—not just physically, but emotionally and psychologically. These films focus on characters who feel disconnected from reality, from others, or even from themselves. Ethereal vocals (or near-whispered dialogue), detached acting styles, glacial pacing, and dreamlike cinematography that places characters in large, empty spaces.

- Under the Skin → An alien walks among humans, but she’s an outsider, unable to truly connect.

- I Am the Pretty Thing That Lives in the House → The protagonist is alone in the house she is taking care of, and her isolation glides into paranoia – or does it?

- Come True → The protagonist struggles with sleep paralysis and distorted reality, unable to trust what she experiences.

- She Dies Tomorrow → A contagious existential crisis spreads, making characters question their own agency and meaning.

- We’re All Going To The World’s Fair → A lonely teenager’s alienation leads to digital self-erasure and transformation.

- Personal Shopper → Grief over her brother’s death nudges a young woman into a distracted, drifting state of mind with one foot beyond the realm of the living.

3. The Fear of Losing Control (of Body, Mind, or Reality)

There’s a hypnotic, creeping horror in the idea that something inside you isn’t yours anymore, whether it’s your body, your thoughts, or your reality.

- Beyond the Black Rainbow → A woman is experimented on, and forced into a meditative, drugged state where she has no control over her own mind.

- It Follows → A supernatural force attaches to one’s body via sexual intimacy, lingering forever.

- Come True → Dreams invade reality, making it impossible to tell what’s real.

- New Religion → A woman’s grief physically alters her, suggesting a loss of control over her own body.

- Lux Aeterna → The film builds to a trance-like hysteria where reality itself dissolves into a photo-epileptic euphoria.

4. The Blurring of Reality and Dream (or Nightmare)

These films create liminal spaces where the boundaries between reality and dream (or nightmare) are dissolved. Slow-motion sequences, uncanny lighting, static long takes, distorted sound design that mimics the way dreams feel, and abstract storytelling. Surreal visual distortions, lingering shots of people staring into nothingness, ambient drones that make scenes feel stretched out, and slow-moving figures, these films blur the boundary between self and other, between the real and the imagined.

- Come True → Dreams take on a physical presence, bleeding into the real world.

- Skinamarink → The entire film is a child’s disjointed nightmare, where logic doesn’t apply.

- Chime → Repetitive sounds and surreal moments distort reality, drawing out the uncanny in everyday.

5. The Body as a Haunted Space

A major theme in shoegaze horror is that the body is not entirely one’s own—whether it’s invaded, manipulated, or controlled by external forces. Close-up shots of skin, hair, and eyes, whispery breathing on the soundtrack, and ambient noise that makes the body feel distant from the self.

- Beyond the Black Rainbow → A woman’s mind and body are altered by strange experiments.

- It Follows → The body becomes a carrier for horror, transforming intimacy into something monstrous.

- New Religion → A woman’s grief manifests physically, as if sorrow can reshape the body.

6. Violence as Something Abstract or Meditative

Unlike traditional horror films, shoegaze horror treats violence as something slow, inevitable, and detached rather than shocking or graphic. Long silences, muffled sound design, and a feeling of passivity in the face of horror—as if the universe itself is indifferent to suffering.

- Lux Aeterna → The implicit violence of the patriarchy erupts into an abstract multicolour strobing effect as the film-within-the-film, the film, Charlotte Gainsbourg, and perhaps reality itself all break down – while shouting and crying dissipate into an endless drone.

- In a Violent Nature → The slasher genre is slowed down to an eerie, meditative pace, making death feel like a natural force rather than a brutal event.

- Skinamarink → Violence is abstract—characters disappear, dissolve, or lose their voices, rather than being conventionally attacked.

- Chime → The horror builds in tiny, surreal ways, making reality feel subtly off rather than overtly dangerous – and the violence, when it comes, is disengaged and passionless.

The Branches and Roots of Shoegaze Horror

Other Shoegaze Horror films (and horror-adjacent films) include the giallo kaleidoscope of The Strange Colour of Your Body’s Tears (Bruno Forzani & Helene Cattet, 2013), the beautiful post-human hypnogogic horror of Upstream Color (Shane Carruth, 2013), Peter Strickland’s The Duke of Burgundy (2014) (even more of a woozy dream than Berberian Sound Studio, although I would say an onanistic mystery-fantasy rather than a horror), Osgood Perkins’s The Blackcoat’s Daughter (2015) aka February, and Panos Cosmatos’s prog rock bloody revenge bad trip Mandy. The oblique plotting and low-key strangeness of some of Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson’s cosmic horror work (e.g. The Endless, 2017) has a degree of crossover.

The roots of Shoegaze Horror are widespread. They include the surreal shorts of Maya Deren (Meshes of the Afternoon, 1943) and David Lynch (The Grandmother, 1970) (and for that matter, his later feature Inland Empire (2006)), the Czech surrealist tradition of Jaromil Jires (Valerie and Her Week of Wonders, 1970) and Jan Svankmajer (Alice, 1988), the atmosphere-heavy low-budget American horrors of the early 1970’s such as Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (John D. Hancock, 1971) and Messiah of Evil (Willard Huyck & Gloria Katz, 1973), the dreamy, drifting films of Philip Ridley (The Reflecting Skin, 1990; The Passion of Darkly Noon, 1995), and the unsettling sensory textures and mysterious narratives of early J-Horror such as Angel Dust (Gakuru Ishii, 1994), Pulse (Kiyoshi Kurosawa, 2001), and the v-cinema that preceded them. The dislocating edits and hypnotic flickers of Kurosawa’s Cure (1997) are also felt, alongside the assaultive visuals and aggressive drone of Begotten (E. Elias Merhide, 1989) and the assorted collapses of memory and reality in Charlie Kaufman’s work (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, 2004; Synecdoche New York, 2008; I’m Thinking of Ending Things, 2020).

One of the strongest influences, though, is Jean Rollin – and of his films it’s probably The Iron Rose (1973) that is most powerful. In this film, Rollins’ purgatorial masterpiece, a young couple wander into an abandoned cemetery at dusk – only to find themselves lost in an endless night where time, space, and sanity unravel. Rollin’s most haunting film, The Iron Rose strips horror down almost to pure atmosphere—a drifting, melancholic descent into the abyss, where graves are welcoming and death feels eerily seductive. With hazy, late-autumnal cinematography, minimal plotting, and rambling dialogue, the slow, poetic unraveling of The Iron Rose is ethereal, eerie, and achingly romantic – even as it leads the audience into the tomb.

There goes that dream

Despite all these attempts to tie it down, Shoegaze Horror is perhaps as elusive as it is immersive—a cinema of ghosts, memories, and slow-burning dissolution where horror is less about what happens than how it feels, vibrating out through time like a drone that never quite resolves. If Folk Horror binds its terrors to the land and Cosmic Horror flings them into an inhuman void, Shoegaze Horror suspends its dread in a thick, hazy ether, somewhere between dream and waking, memory and oblivion. It is a cinema of spectres, of things half-imagined but deeply felt. These films resist easy definition, just as they often resist conventional pacing, resolution, or the sharp shocks of traditional horror. It is a cinema of depersonalisation, derealisation, and depression. It is a genre that lingers, loops, and dissipates, grazing against our perceptual filters, fading and reverberating as it goes. These films are not always something for a viewer to actively watch so much as something for them to sink into; something that surrounds you, drifts through you, and leaves you haunted… if only for a little while.

As for that couple at the cinema – well, with which of them do you sympathise?

This is a compelling and well-articulated thesis; bonus: your list of film selects put me on to a handful of films that are brand-new to me!

I had a similar thought marble rattling around in my noggin for the past six months or so, but from a different musical angle: the hauntology genre and the Ghost Box label. I (precariously) tethered this framework to films like Censor (technostalgia), Possum (overlapping past/present), and Enys Men (the body as source of mystery/fear, metaphysical nightmare state). I think all three films could easily slip into your shoegaze horror genre construct as well.

Thanks for this — cheers!